In her simple Vesak message, Ayyā Medhānandī Bhikkhunī said at the Ottawa

Vesak Festival to commemorate Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and death on 2nd

May 2015 at the Ottawa City Hall;

In her simple Vesak message, Ayyā Medhānandī Bhikkhunī said at the Ottawa

Vesak Festival to commemorate Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and death on 2nd

May 2015 at the Ottawa City Hall;

“It is the inner journey to understand self and the nature around us

that helps us find happiness rather than the world of external gratification.”

The native of Montreal, is a former international humanitarian worker

and the founder of the Sati Sārāņīya Hermitage, a Theravada Buddhist training

monastery for nuns in Perth, Ontario.

She also expounded on the importance of a core practice of meditation, along with moral behaviour, to enable wisdom to realize and deal with our three defilements – ignorance, attachment (craving and clinging) and aversion (hatred).

|

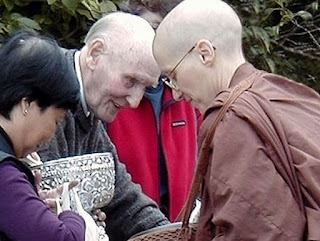

| Ayya Medhanandi Bhikkuni Satisaraniya |

While this is part of the essential practice for a Buddhist monk, her

message was for us lay people to consider a personal practice towards

mindfulness to discern the good from the not so good. This could lead to peace with self and others

by dealing with our own defilements.

I have a special reverence for those who relinquish the modern consumer

culture to follow the path of the Buddha as a monk. What a difficult challenge it must be to give

up our primal nature for power, pleasure and to procreate.

I have known many monks in my lifetime. I met often, my father’s spiritual

friends like the Sri Lankan scholar monk Venerable Piyadassi, the German born

Venerable Nyanaponika and Richard Abeysekera (who might as well have been a

monk) who devoted his life to the Buddhist Publication Society (BPS) in

Kandy, Sri Lanka. A scene like the three of them in

this photo at BPS is vivid in my memory.

I realize what a privilege it was to associate with them from an early age and to later learn

about their lives and teachings through reading and listening to stories.

Walks through the

Forest

I looked forward to the walks with my father through Kandy’s pristine

forest, Udawattakele to visit Venerable Nyanaponika’s hermitage when I was

about 6 years old.

(Thirty years later, while running a solar energy business in Sri Lanka, I was so happy to instal a solar electric system at this hermitage when American monk and scholar Bhikku Bodhi was there.)

The first time I remember seeing my father and Venerable Nyanaponika in a meditation trance in their lotus position - their stillness scared me, as I thought they were not breathing. I had my first conversation on meditation with my father after that.

(Thirty years later, while running a solar energy business in Sri Lanka, I was so happy to instal a solar electric system at this hermitage when American monk and scholar Bhikku Bodhi was there.)

The first time I remember seeing my father and Venerable Nyanaponika in a meditation trance in their lotus position - their stillness scared me, as I thought they were not breathing. I had my first conversation on meditation with my father after that.

Venerable Nyanaponika, a Jewish German saw what was coming in Germany, made his way to Sri Lanka in the 1930s. He became a monk in 1936 under the

tutelage of a fellow German, Ven Nyanatiloka (a former violin

virtuoso Anton Gueth) who came to Sri Lanka in 1910 and established the Island

Hermitage for western monks in the southern coastal town of Dodanduwa.

Venerable Nyanaponika, a Jewish German saw what was coming in Germany, made his way to Sri Lanka in the 1930s. He became a monk in 1936 under the

tutelage of a fellow German, Ven Nyanatiloka (a former violin

virtuoso Anton Gueth) who came to Sri Lanka in 1910 and established the Island

Hermitage for western monks in the southern coastal town of Dodanduwa.

Venerable Nyanaponika, was a great teacher and wrote many books on Buddhism

and especially on the practice of mindfulness and meditation.

He wrote this in his book The

Power of Mindfulness.

“One must know mindfulness well and cultivate its

acquaintance before one can appreciate its value and its silent penetrative

influence. Mindfulness walks slowly and deliberately, and its daily task is of

a rather humdrum nature. Yet where it places its feet it cannot easily be

dislodged, and it acquires and bestows true mastery of the ground it covers.”

I was influenced from a young age to carve out a sacred time and space for

a regular personal practice. I started

exercising and running daily from the age of 13 and included a meditation

practice. Even though the

morning push-up and sit ups dominated the later teen years and

twenties, I managed to sit in meditation at least 3 times a week, to keep my

practice alive.

Monk and his

Motorcycle

In the 1980s in Canada, while at Seneca College studying Mechanical

Engineering Technology, I cultivated a friendship with a young Jewish Canadian

investment banker and motorcycle enthusiast turned Buddhist Monk, Bhante

Vannassara at the Toronto Mahavihare Temple in Scarborough.

His transformation from a heady life to a monk’s journey was fascinating, as I

related well to his former life and intrigued by his current. He provided intimate insights into renouncing

all the things I enjoyed, to wilfully follow the path of the Buddha. We had hours of conversation, usually in the

evening, about what motivated him, what was happening to him -

his thoughts, feelings and needs - as he focussed on the practice. We often meditated together and discussed

different aspects of the practice – focus, concentration, attention to quell fleeting

thoughts and Vipassana – learning to see things as they are.

One evening, he interrupted an interesting discussion with, “that sounds like a Kawi 900, one the fastest bikes in the world and that was

my last one” as a motorcycle zoomed by the temple. He told me stories of how he would dare to

take Toronto’s Don Valley Parkway – Gardiner Expressway’s sharp banked ramp

as fast as he could, sparks flying from the foot pedal.

He was not satisfied with the lack of meaning of the material world, so he was testing the edges of life with a machine. Then he found that he could do the same by going inward through path of a monk. Our conversations and my own inquiry revealed how challenging it must be to go against the grain, so I admired him much for renouncing the superficial temptations of life.

As he advanced in his practice, put his Kawasaki motorcycle behind, he moved to a forest in the south of Sri Lanka around the same time I established

myself in Colombo. I met him once a year in Colombo, as he came

to renew his Sri Lankan Visa.

As he advanced in his practice, put his Kawasaki motorcycle behind, he moved to a forest in the south of Sri Lanka around the same time I established

myself in Colombo. I met him once a year in Colombo, as he came

to renew his Sri Lankan Visa.

I saw his gradual inward retreat as his spiritual journey

advanced. A group of friends and well

wishers helped him to publish his book Wind

Not Caught in a Net, which is a difficult read. I keep going back to it as I advance in years

and try to make sense of his deep treatise.

He has since moved to Myanmar to find more peace in deeper jungles for

his continuing spiritual journey.

The Mahamevnawa

Movement

More recently, before I moved back to Canada in 2011, I spent a day at a

Mahamevnawa Temple in Matara, in a picturesque hilly property of hundreds of

acres in the south of Sri Lanka. I went

at the invitation of industrialist Tissa Jinasena, the benefactor who built the

temple. He continues to manage the infrastructure and its utilities, so the

monks can follow the authentic path of the Buddha in peace.

The Mahamevnawa movement was started by Venerable Kiribathgoda Gunananda to propagate the authentic teachings of the Buddha, the Tripitaka

Dhamma[i] in its original form, when

it was seen as getting misdirected in Sri Lanka. The temple welcomes any person, of any race

or religion to go through the process to ordain as a monk. Meditation and a life of virtue (sila) is the cornerstone of their

practice to surrender the mind to understand the true nature of life.

I had a fascinating conversation with Venerable Nawalapitiye Ariyavansa,

the chief monk of the Matara monastery.

Ariyavansa Thero was a former finance professional as many of the monks

are also former doctors, engineers and university students among others from

various backgrounds and walks of life. I

was not surprised then to see their use of modern technology and social media

to spread the Dhamma.

Learning from real

Stories

My recent reading about many western monks who renounced their

worldly life in books such as Seeing the

Way – An Anthology of Transcribed Talks and Essays by Monks and Nuns of the

Theravada Forest Sangha Tradition and a similar book Friends on the Path - Dhamma Reflections from Ajahn Sundara and Ajahn

Candasiri, reinforces meditation as the core practice to this path. Most of these monks were disciples of revered monk, Ajahn Chah of Thailand.

Their incredible journeys of giving up what we take so for granted –

family, roof over their head, a place to sleep, carnal desires, food, security

and safety from predators – are reflected so vividly in these stories.

Bhante Kovida, Jamaican born wandering monk and I have become friends over the last 4 years and his book The World is Myself - A Monks Travel Journal captivated me with wonderful tales of his travels. The stories are interspersed with great wisdom he acquires from his mind and body practice where meditation and tai chi qigong is core.

He introduced mindfulness to Health Canada in Ottawa, which has been received so well as a tool to deal with workplace challenges and uncertainties.

Bhante Kovida, Jamaican born wandering monk and I have become friends over the last 4 years and his book The World is Myself - A Monks Travel Journal captivated me with wonderful tales of his travels. The stories are interspersed with great wisdom he acquires from his mind and body practice where meditation and tai chi qigong is core.

He introduced mindfulness to Health Canada in Ottawa, which has been received so well as a tool to deal with workplace challenges and uncertainties.

Importance of the

Meditation Practice

The Noble Eightfold Pathway is central to their journey as meditation – concentration

leads to mindfulness. Mindfulness leads

to right view, wisdom, and right thoughts.

Right thoughts lead us to a life of virtue – right words and action and

to a right livelihood.

These monks show how they learn to act with virtue in the world, when

they realize through their wisdom that karma – the cause and effect – the

action and result of life, is all pervading.

The other realization is that all phenomena, whether mental or physical

in this universe is impermanent (anicca).

Nothing is permanently satisfying or dependable.

I grew up knowing these simple truths on one hand and eventually realized

that the material world is counter to this.

I straddle both worlds keeping my senses open in inquiry, as competition tends to dominate my reptilian survival nature. The challenge is to find balance with my compassionate nature - open my heart to loving kindness, generosity and to live a life of virtue.

Yet, I realize nothing is permanent and nothing is for sure – the delusion of certainty creates the suffering, if I am not mindful.

This way I try to keep a check on the three defilements - ignorance, aversion and attachment. As they ebb and flow, the notion of scarcity creates anxiety for the future, nudging me towards the edge to grasp and cling.

I straddle both worlds keeping my senses open in inquiry, as competition tends to dominate my reptilian survival nature. The challenge is to find balance with my compassionate nature - open my heart to loving kindness, generosity and to live a life of virtue.

Yet, I realize nothing is permanent and nothing is for sure – the delusion of certainty creates the suffering, if I am not mindful.

This way I try to keep a check on the three defilements - ignorance, aversion and attachment. As they ebb and flow, the notion of scarcity creates anxiety for the future, nudging me towards the edge to grasp and cling.

Hence, the struggle continues to find that balance to discern between want and need, to keep greed in check and to live with virtue – as

money and material life has its utility, especially when I have a family to

nurture.

I know it is my daily meditation, reflection and the quiet time that helps to balance that dissonance within myself.

I know it is my daily meditation, reflection and the quiet time that helps to balance that dissonance within myself.

It is a joy to be among these monks and nuns, steadfast on this path, to learn from them about

their journey as they transcend the worldly life and find that state of

happiness and peace on their path to enlightenment. When I realize our common humanity, I know I have choices too about how I may show up in the world.

I am inspired by them to continue the mindfulness practice and inquiry without expectation and with patience as I learn to discern right view, right thought, right words and right actions.

I am inspired by them to continue the mindfulness practice and inquiry without expectation and with patience as I learn to discern right view, right thought, right words and right actions.

We forgive, we let go of those memories, because taking

refuge in Sangha means, here and now, doing good and refraining from doing evil

with bodily action and speech. Bhikku Sumedho

Buddham saranam gacchami

I go to the Buddha for refuge

I go to the Buddha for refuge

I go to the Dhamma for refuge

Sangham saranam gacchami

I go to the Sangha for refuge.

I go to the Sangha for refuge.

[i] Tripitaka

means "three baskets," from the way in which it was originally

recorded in the 3rd century BC. The text in Pali was written on

long, narrow Ola leaves,